Major Depressive Disorder: Report accurately, and shore up the medical record against denial

By Brian Murphy

Large caveat to the following: I am not a clinician, nor a coder, though my work frequently brushes up to clinical coding.

I was having a recent conversation with my colleague Jason Jobes for an upcoming episode of Off the Record, during which we touched on OIG audits of HCCs and unsupported diagnoses as an audit target. One of these is major depressive disorder (MDD).

For example, MDD was described as a “high risk diagnosis” in a September 2022 OIG audit of Highmark Senior Health Company. The OIG stated that of 30 sampled enrollee years for the DX, eight were in error (a 27% error rate). The OIG then offered an example of what it considered to be an error—no documented treatment:

An enrollee received one major depressive disorder diagnosis (which maps to the HCC for Major Depressive, Bipolar, and Paranoid Disorders) during the service year but did not have an antidepressant medication dispensed on his or her behalf. In these instances, the major depressive disorder diagnoses may not be supported in the medical records.

Coupled with the fact that May is mental health awareness month, I felt prompted to weigh in with some thoughts, and a poll.

There is a series of ICD-10 F codes for reporting MDD, with severity stratification in the code descriptions. For example:

- F32.0 MDD, single episode, mild

- F32.1, MDD, single episode, moderate

- F32.2: MDD, single episode, severe without psychotic features

These continue all the way up and including F32.9, MDD, single episode, unspecified.

The F33 series specifies MDD recurrent, both current and in remission. Most of these codes group to CMS-HCC 59 (Major Depressive, Bipolar, and Paranoid Disorders) in version 24.

ICD-10Data.com has a wealth of clinical information on MDD, including a list of symptoms to refer to if a physician has not documented the diagnosis (as I understand it some physicians avoid the term out of fear of patient labelling), as well as clinical information and code history. And of course, the gold standard is the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders V (“DSM-5”), which states that MDD can be either mild, moderate, or severe. This underpins the ICD-10 code set.

All of which is very helpful to CDI and coding professionals. But, from what I can deduce, what constitutes “enough” clinical support to satisfy payers and auditors and prevent MDD denials is quite subjective.

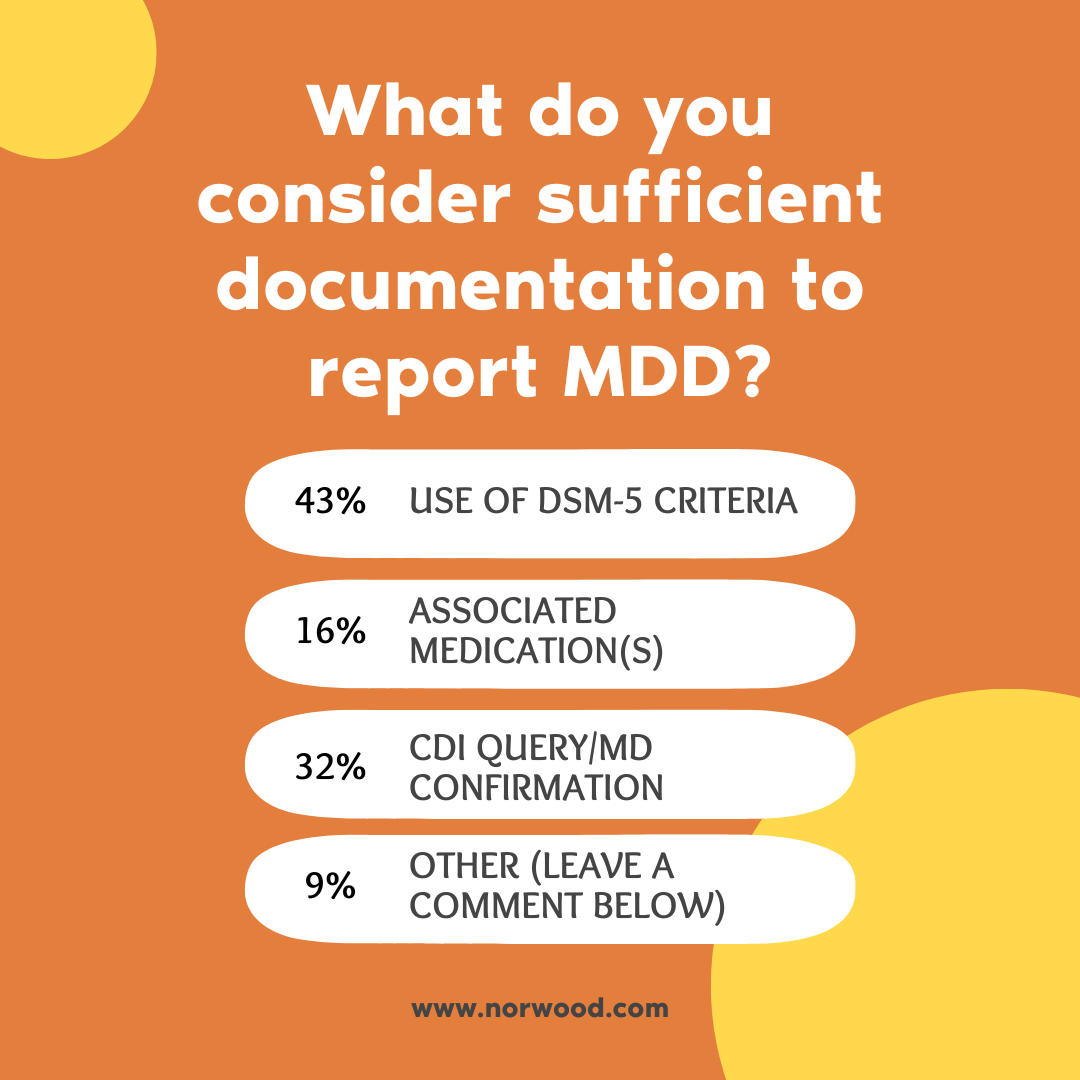

So I asked the following poll on LinkedIn. Not only did the poll generate 93 answers, but I got some incredibly helpful comments and suggestions that I’m including here.

What do you consider sufficient documentation to report major depressive disorder?

Use of DSM-5 criteria 43%

Associated medication(s) 16%

CDI query/MD confirmation 32%

Other (leave a comment below) 9%

Here are some sample comments, one each from the physician, RN CDI, coding, and case management perspective:

(James Kennedy, MD): Severe depressive disorder often requires intensive outpatient or inpatient treatment, cognitive behavioral therapy, and other modalities other than writing a Prozac script. Not uncommonly, drug/sex addiction accompanies it as well as bipolar behaviors, PTSD manifestions, and other unmanageability. I agree with Christy Grimm of the OIG that major depressive disorders are over documented, a circumstance promoted by ICD-10-CM and unfamiliarity with DSM-5-TR criteria. Clinical validation of this documented diagnosis is often indicated.

(Michelle Wieczorek, RN, RHIT, CPHQ, CCDS): There is no such thing as “over documenting a diagnosis” that has active treatment. That’s monitoring. There is a reason we need this diagnosis documented and it is because there is plenty of actuarial and clinical evidence that supports that depressive disorders impact patient outcomes and healthcare spend. Depressed patients with chronic lung disease have higher healthcare spend. Look at MDD in Elixhauser. Of all the diagnoses that we have started to get right, this is one that the actuarial model doesn’t like because of how it effects spend…the inverse of why we risk adjust.

(Jen Stinnett, RHIA, CRC): What isn’t addressed in the report, but we all know is part of the problem, is the challenge of providing interim support to ensure the patient is able to get into a mental health provider, that they make the appointment, and keep the appointment. Some of our docs absolutely provide med management for depression, some do not. There is a lack of mental health support in general, especially in rural areas. It’s a huge challenge to best support these patients who are clinically depressed. My opinion from experience is not the lack of coding or documentation (always a work in progress, right!) It’s more about a larger issue of addressing community needs and support for our doctors.

(Angela Walby, MBA, BSN, RN, CCM): Many times patients screen positive when it is circumstantial. Many with true long-term depression simply refuse medication or treatment. Sometimes, they are self-treating with exercise, hobbies, meditation or other therapeutic methods. It’s important for the provider to discuss their screening results, offer treatments/medications/referrals and then clearly document the discussion. This would include documentation of any therapeutic methods the patient is currently using.

So I ask you, reader: What do you want to see in the documentation before you pick up MDD? What “meets” your MEAT (monitored, evaluated, assessed, treated) criteria?

Hopefully you pick up some ideas here that will guide you in your practice.

Reference

OIG report: https://oig.hhs.gov/oas/reports/region3/31900001.pdf

Related News & Insights

Clinical Clarity: Navigating Problem Lists and Defensible Narratives with Dr. Trey LaCharite’

Listen to the full episode here: https://spotifyanchor-web.app.link/e/mQEUhXavSIb If you’ve ever been a member of ACDIS you’ve almost…

KDIGO Announces new Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of CKD

By Brian Murphy According to the ACDIS 2023 CDI Week Industry Overview Survey, kidney disease was ranked…